You are here

Microcosms: Peter D. Gerakaris Shares a Grander Scheme of Things

Microcosms: Peter D. Gerakaris Shares a Grander Scheme of Things

From inside his art studio in an old farmhouse he rents in Cornwall, Conn., Peter D. Gerakaris recently witnessed for the first time the power and poise of a bird that, for good reason, has been a recurring theme in his many works: the falcon, this one a peregrine falcon.

In a burst of brutal purpose, it swooped from a misty hilltop down to a field beside the Housatonic River, snatched a rodent with its talons and soared off into the vanishing point.

“It blew me away,” Gerakaris recalled.

In Greek, his family name, Gerakaris, translates to “falconer.” His Greek grandmother, YiaYia, would have visions and dreams about flying, he said. “So, I personally regard the falcon as her presence.”

For an artist whose work draws attention to — and seeks to mend — the fundamental interconnectedness of all living things, this ephemeral grab-and-go served as a good sign. Gerakaris, 43, clearly had found a healthful location to encamp and begin arguably the most profound and prolific period of his artistic career.

His creations here over the span of three years have transcended conventional boundaries, bushwhacking instead along the enigmatic contours between the ethereal and physical, all underscored by his singular resolve to enlighten, delight and incite.

These efforts — these discoveries — culminate this summer with “Microcosms,” his solo exhibition of mixed-media artworks in Berkshire Botanical Garden’s Leonhardt Galleries from June 8 through Aug. 4.

A ‘Part,’ Not ‘Apart’

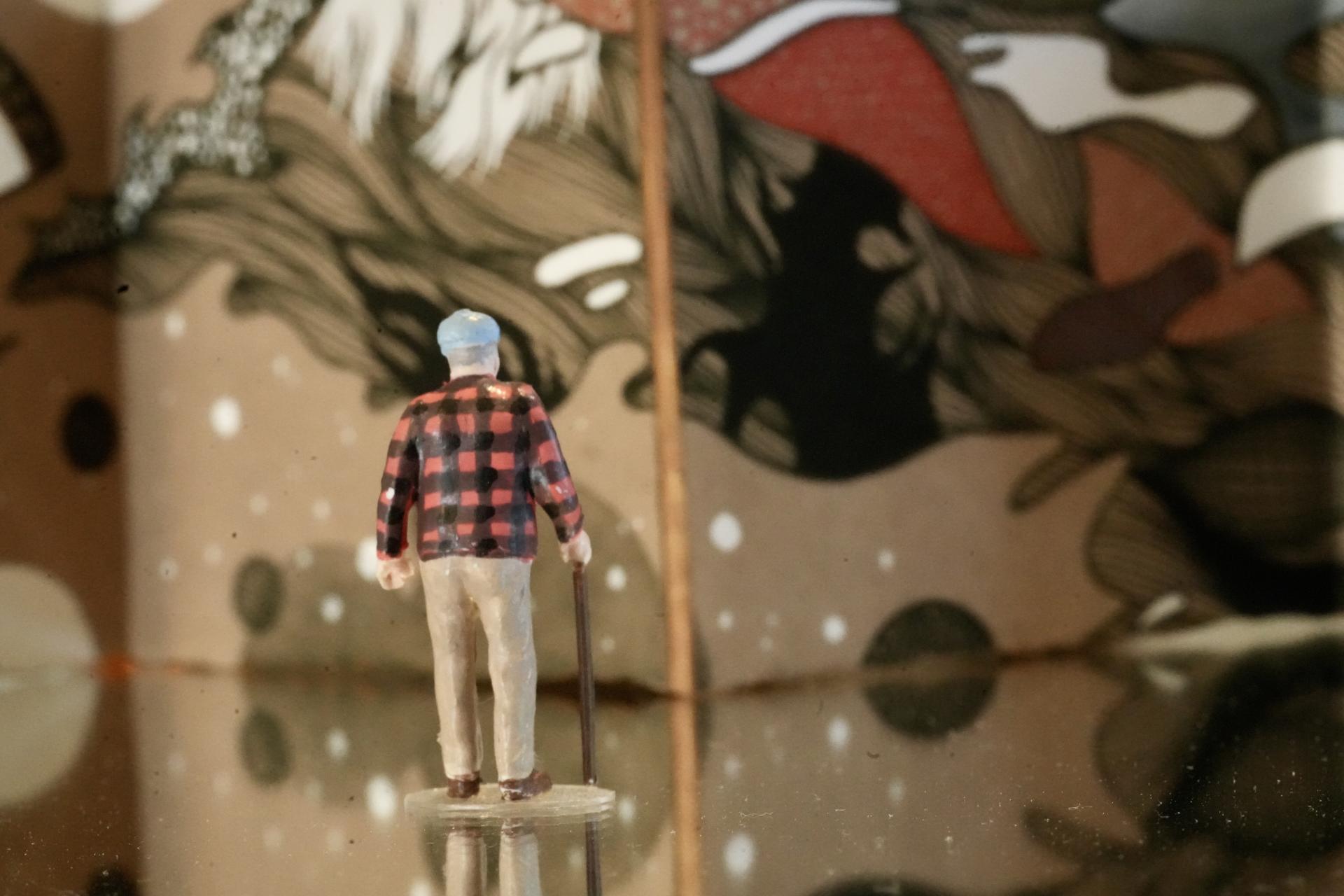

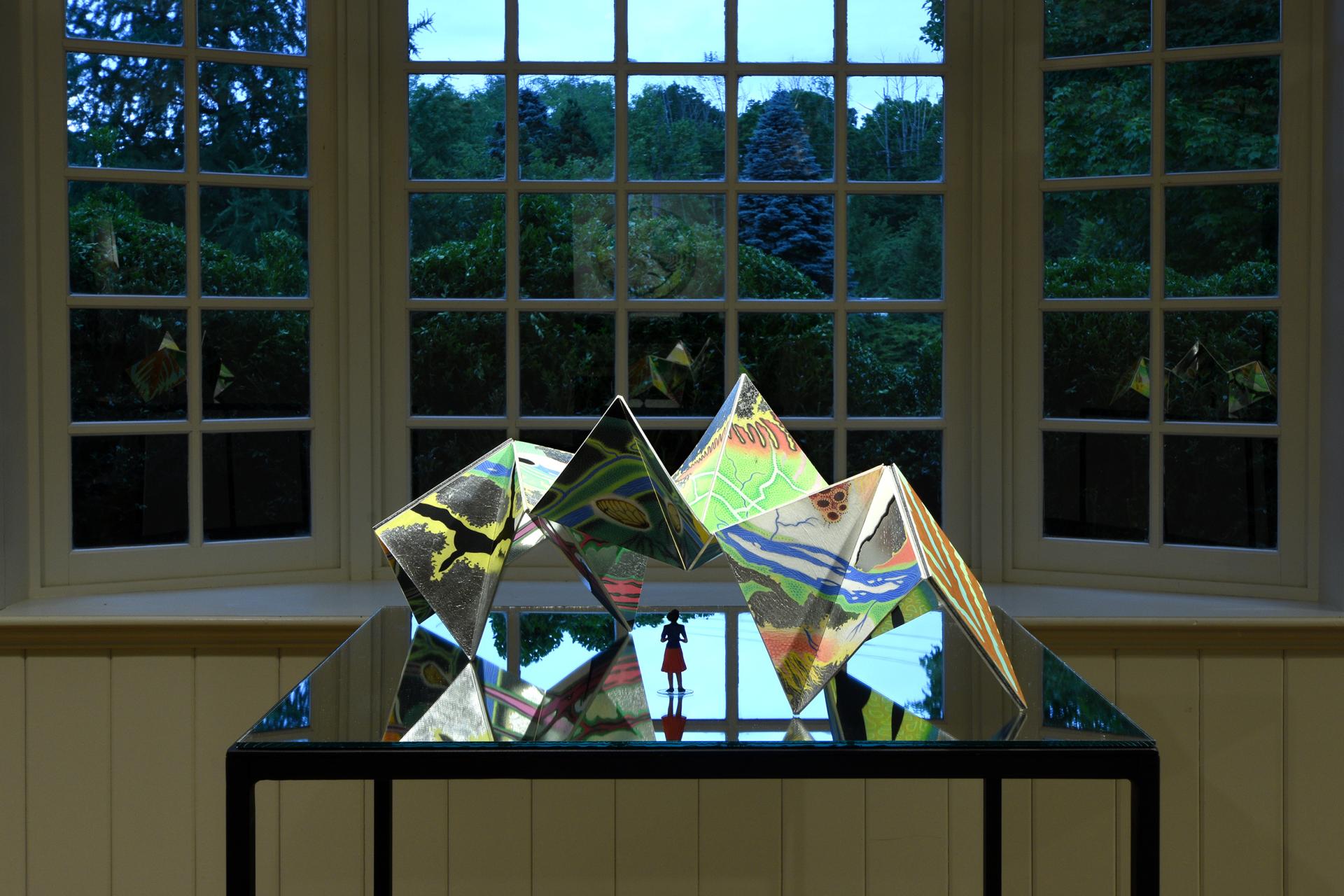

A journey of reverence and wonder, “Microcosms” includes dynamically colored icons and mosaics created by means of old-world techniques as rare and endangered as the flora and fauna they depict. Gerakaris also includes several of his botanical/topographical works in tondo (circular paintings), origami sculptures and hand-embellished prints and works on paper.

“Each work functions more like its own miniature world, or microcosm, while simultaneously sharing a strong common thread with all the other works,” said Gerakaris, who earned a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from Cornell University and a master’s degree in fine arts from the City University of New York Hunter College. His works over the years, including large-scale public installations, have been exhibited around the world. They are showcased in various permanent institutional and private collections.

The creator of the “Spotted Owl Mosaic,” an installation that has resided in BBG’s Vista Garden since 2021, Gerakaris sees “Microcosms” as a bit of a homecoming.

“BBG and I of course share the philosophy that humanity is not apart from nature but rather a part of nature,” he said. “As soon as that philosophical shift happens on a grander scale, we are less likely to destroy nature, less likely to destroy ourselves.”

‘Free-Range’

His esteem for the beauty, complexity and vulnerability of the natural world was ingrained from the start. The only child of professional artists and avid gardeners, Gerakaris describes his upbringing in the New Hampshire woods just outside the cultural hothouse of Dartmouth as “free range.”

He was delivered into this world on the barter system; his parents paid the doctor with artistic metalwork his father had hand forged. Craftsmanship, resourcefulness and the human touch were essential elements of his upbringing. Playing on the family drafting table as a child, he learned to draw and improvise through a surrealist call-and-response “doodle game.” (Incidentally, the family took numerous trips to BBG.)

Gerakaris wanted to be a professional baseball pitcher, but an injury scotched that dream. His “fallback plan” was art. Drawing and art making had always been an outlet for him. He discovered he could create his own worlds that he could inhabit and explore.

“I’m living the fallback plan, a far different pay scale,” he said with a laugh.

Following his undergraduate work, the natural world would become the central theme in his art all due to “a startling slap in the face” in an unlikely setting: Beijing.

He had received an artist’s grant and residency in China in 2005. He had imagined he would step off the plane in Beijing immersed in a paradise of red lacquered pagodas, lush landscapes and rivulets of rickety bicycles. Instead, coal smoke was everywhere. The roads were car-choked. His assumptions of ancient paradise were smothered in freshly minted high rises and asphalt.

“I was desperately looking for a touchstone,” Gerakaris recalled, “and I found myself wandering into some of the few preserved historic sites in Beijing, like the garden at the apex of the Forbidden City. There, I just had this profound awakening: Wherever I find nature, I feel at home. I realized I had taken for granted the environment I’d grown up in, of having a garden, eating your own vegetables, living amidst nature.”

Up until that point, his art had focused on geometric forms, urban spaces and playful shadows — nothing at all resembling the luminous, mysterious, nature-based work that was to come.

Preparing for ‘Microcosms’

In his studio in early spring, Gerakaris was in typical form: a multi-tasking maestro of spontaneity and experimentation. He sorted through completed projects while beginning new ones for “Microcosms,” each destined to be adorned with intricate details: delicate tendrils, floral weaves, vibrant blooms, stoic birds, and flitting insects — new worlds!

His tondos blur the line between a telescope’s magnification and a microscope’s scrutiny. Each fold of his origami sculptures contributes to a cohesive narrative inspired by natural cycles.

All his works pay solemn fidelity to the obligations we owe to the earth and its inhabitants, but none more so than his icons. He learned the ancient art form as an undergraduate while briefly studying in Rome. One workshop focused on the creation of a religious icon in the traditional style that emerged during the Byzantine Empire in the 4th century. Equipped with a wooden board, egg tempera, white gesso, rabbit skin glue, and gold leaf, he created a tender portrait of Madonna and Child that he would later gift to his grandmother, YiaYia. She had a priest bless it. She would cherish it — by her bedstand — until her death in 2015.

Despite being agnostic, Gerakaris felt an immediate connection to Byzantine religious iconography. He appreciated its historical and cultural significance, careful and precise artistry, vibrant colors, and symbolic imagery. His visit to his great-great grandparents’ home in Crete and nearby austere monasteries ornamented only with icons, filled him with awe and wonder — and an idea that later would become a central theme in his work.

Instead of depicting religious figures, Gerakaris turned to iconography beginning in 2017 to honor endangered or rare flora and fauna, taking these species and their habitats and transposing them as tangible, wondrous representations in a neo-Byzantine icon context. This unconventional approach infuses his work with a timeless, transcendent quality grounded in urgent, earthly concerns. He forces us to question our assumptions. He blends tradition. He bends tradition.

Much like how religious icons historically have sought to make the divine tangible and relatable, Gerakaris’ icons evoke a sense of connection and duty towards safeguarding our planet’s astounding kaleidoscope of interwoven life.

“Microcosms” also will include mosaic icons translated into cut glass and presented like gemlike fragments as if unearthed from ancient ruins. These pieces are the result of collaboration with mosaicist Stephen Miotto, who helped translate Gerakaris’ original “Spotted Owl” icon into the “Spotted Owl Mosaic” at BBG.

Back in his studio, time is ticking. Gerakaris has an exhibition to continue preparing for. Next up: creating an icon depicting the rusty patched bumblebee, a species in precipitous decline since the 1980s due, at least in part, to pesticide use and habitat destruction.

“The rusty patched bumblebee is the first bumblebee to be added to the list of endangered species,” Gerakaris said with a sigh.

He has prepared the board in the manner ancient monks would have prepared a board for iconography — every painstaking step a form of meditation. If a peregrine falcon is circling overhead, he hasn’t the time to look now. And he doesn’t need to.

Would his devout Greek Orthodox grandmother, YiaYia, approve of his recent work?

“I could hear her saying, ‘Now that’s really different. Look at all those colors!’ Gerakaris said. “Yes, I really believe she’d approve.”

Help Our Garden Grow!

Your donation helps us to educate and inspire visitors of all ages on the art and science of gardening and the preservation of our environment.

All Donations are 100 percent tax deductible.